From time to time, we hear of the demolition of an historic or architecturally significant home in the news. Inevitably there’s an outcry. Members of the community are understandably upset. Community leaders agree that “something must be done.” But what?

Shaming a Buyer Who Tears Down a Home Has Never Saved a Home. These Five Preservation Steps Will Save Homes.

In this article you will find five tried and true steps that I have found effective in saving historic and architecturally significant homes over my 45-year professional and civic career, much of which I have devoted to revitalization, preservation and Organic Urbanism—the positive evolution of cities.

When a bulldozer pulls up to a historic or architecturally significant home it’s too late to complain. These futile cries will have no impact on the inevitable. At this point, huge investments have been made, a direction has been sent, and the property owner is dealing with an asset that is often a homeowner’s largest individual holding and most emotional investment.

Historic and Architecturally Significant Homes are Most Successfully Preserved When Everyone Benefits

When preservation is implemented as a punishment tool, preservation is rejected and discord is fostered. This is why it is so important for preservationists to take proactive steps to provide an economic advantage that motivates homeowners to preserve historic and architecturally significant homes.

Five Proactive Preservation Steps that Will Save Historic and Architecturally Significant Homes and Benefit the Homeowner

Community leaders and concerned residents can take these steps to save historic and architecturally significant homes.

- Individual preservationists, neighborhood organizations, architects and preservation groups should identify and illuminate the historic and architecturally significant neighborhoods and homes in the community.

- Community stakeholders and preservationists should contact the homeowners and cultivate their potential interest in preserving their historic and architecturally significant homes when the time comes for their homes to be sold.

- Preservationists and stakeholders should encourage and coordinate architects and interior designers to create preliminary sketches on how best to approach renovations for a specific historic or architecturally significant home to maintain its character and optimize its value in the marketplace. Architects and interior designers with an interest in preservation might donate their services. Nonprofits, preservationists and realtors might underwrite these design services to help save the home.

- Preservationists should encourage contractors, inspectors and appraisers who have an interest in preservation to donate their services to determine the condition of a home and the approximate cost of renovating the home and the economic viability and value of the home once renovated.

- Realtors should work with homeowners, attorneys and title companies to write deed restrictions and easements on a specific historic or architecturally significant home that will allow renovations but prevent architectural devastations when the property is sold to the next owner.

Identifying Historic and Architecturally Significant Homes is the Foundation of Additional Preservation Steps to Saving Homes

In this article I will discuss step one of saving homes, as this step is the foundation of the second, third, fourth and fifth steps of preservation.

Step One – Inventory and Illumination of Historic and Architecturally Significant Homes and Neighborhoods is Foundation of Preservation Success

Individual preservationists, neighborhood organizations, architects and preservation groups should illuminate the historic and architecturally significant neighborhoods and homes in the community.

This is the most important step. Identify neighborhoods that have homes worth saving, take an inventory and then identify and illuminate those homes and their attributes. Make sure everyone in the community knows which homes should be saved and why. Only with an understanding of the neighborhood’s historic and architecturally significant homes can a strategy be put in place that allows the next four steps to occur. Here are several powerful examples and approaches to identifying and illuminating homes and neighborhoods that ultimately saved homes.

First Survey of Old East Dallas Restoration Area

Identifying historic homes made a dramatic impact on a deteriorated 100-block area of Old East Dallas that was destined to be demolished. This multifamily zoned area was comprised 2,000 lots of mostly falling down four-unit apartment houses. However, these 2,000 structures were mostly historic single-family homes that had been retrofitted into and disguised as apartments.

Survey Identifying Original Historic Single-Family Homes Changed Perception of the Area

I recall driving the area block by block with city planner Mike Finley, who created a map with the lots that had a structure that was originally a historic single-family home colored brown. Rather than a map showing lots being used as apartments, the map clearly showed the area was predominantly original single-family homes. This map changed the perception of the property owners, lenders, FNMA, the mayor and City Council, as they could see this was one of the largest collections of early 20th century historic homes in the city and an area worth preserving and revitalizing. Identifying these original historic single-family homes led to the area being rezoned single-family, the area being chosen by FNMA for its first inner city loans in the country, and this 100-block area becoming three individual Dallas historic districts.

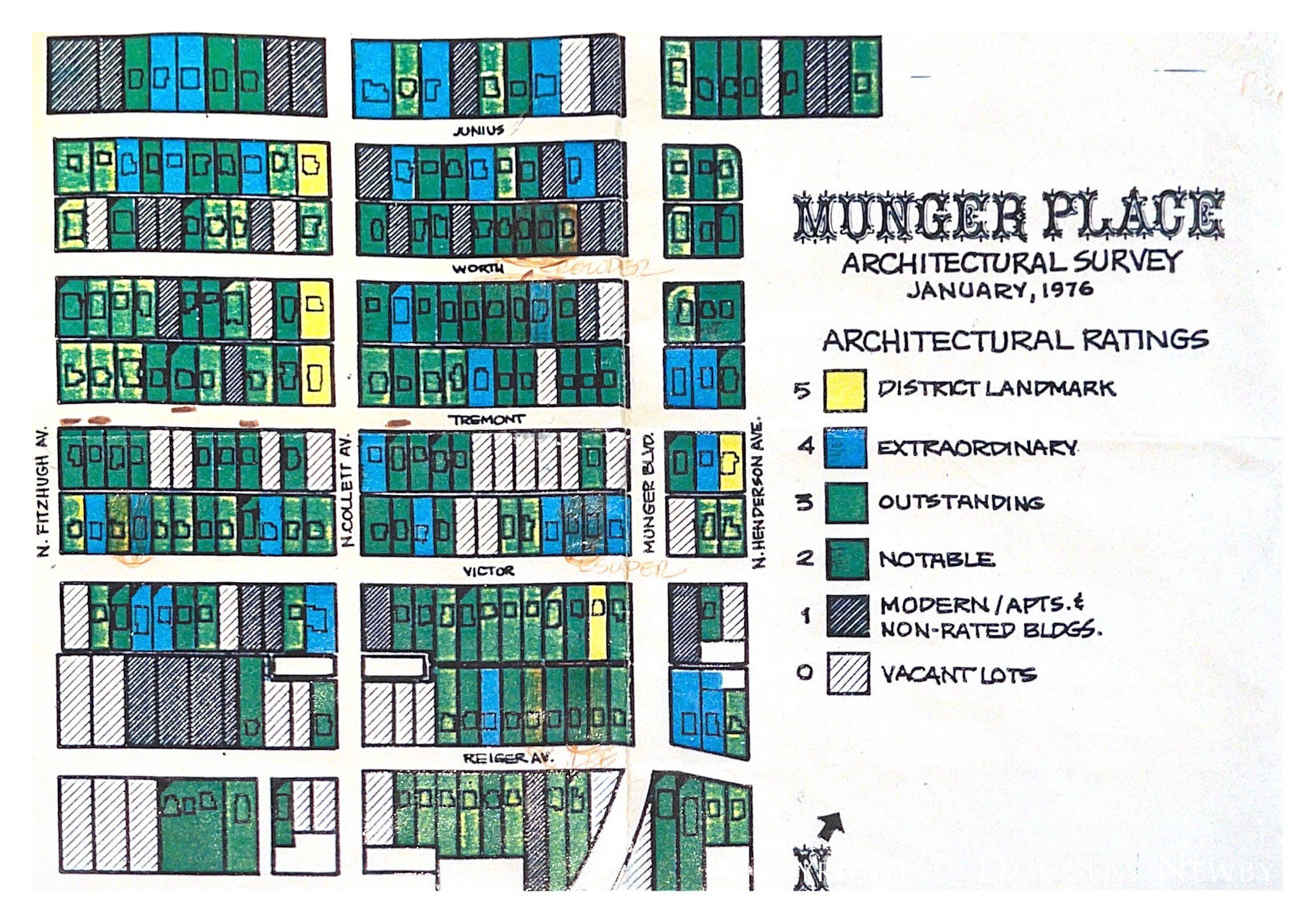

Survey Ranking Architectural Contribution was Helpful in Saving Homes

Another effective vehicle for saving homes is to illuminate homes by doing a survey ranking the architectural contribution of each home. Architects Michael Wayland Brown and Ed Beran, FAIA, did this for Munger Place on behalf of the Historic Preservation League in the 1970s. This survey was included when Munger Place submitted an application to be placed on the National Register of Historic Places, which was granted. This historic designation gave additional momentum to the Munger Place homeowners who were working to have Munger Place become the first single-family zoned historic district with historic design requirements in Dallas. Ed Beran sent me the map survey when he was cleaning his office shortly before his death. I keep the map framed in my library as a reminder of how illuminating homes saves homes

Judy Dooley Created Architectural Survey of Swiss Avenue for UTA Master’s in Architecture

The story of Swiss Avenue’s renaissance in the 1970s and 1980s is a very good example of how identifying the architect, style and history of the homes in a neighborhood helps foster enthusiasm for preserving homes and their architectural quality. In 1978, architecture student Judy S. Dooley created an early architectural survey of historic homes on Swiss Avenue for her master’s thesis at the University of Texas at Arlington. In this thesis, she identified the original architect, architectural style, year built, and the original owner of each home on the Swiss Avenue boulevard. Judy Dooley was never given any formal recognition or awards for her work, but it had a profound effect on me and impact on the buyers who purchased homes on Swiss Avenue. At a time when no realtors in Highland Park were identifying the architects of Highland Park homes they listed for sale, I was able to give potential Swiss Avenue buyers the name of the architect who designed the home that they were considering to buy. This was important because in the early years of the Old East Dallas revitalization, buyers were taking a huge risk and faced many warnings not to move into the Swiss Avenue neighborhood. Knowing that one of the best architects in Dallas had designed the home made it easier for buyers to commit to the process of buying and renovating the home. Judy efforts paid off – she and her husband Richard and their children lived in a magnificent C.P. Sites architect-designed home on Swiss Avenue.

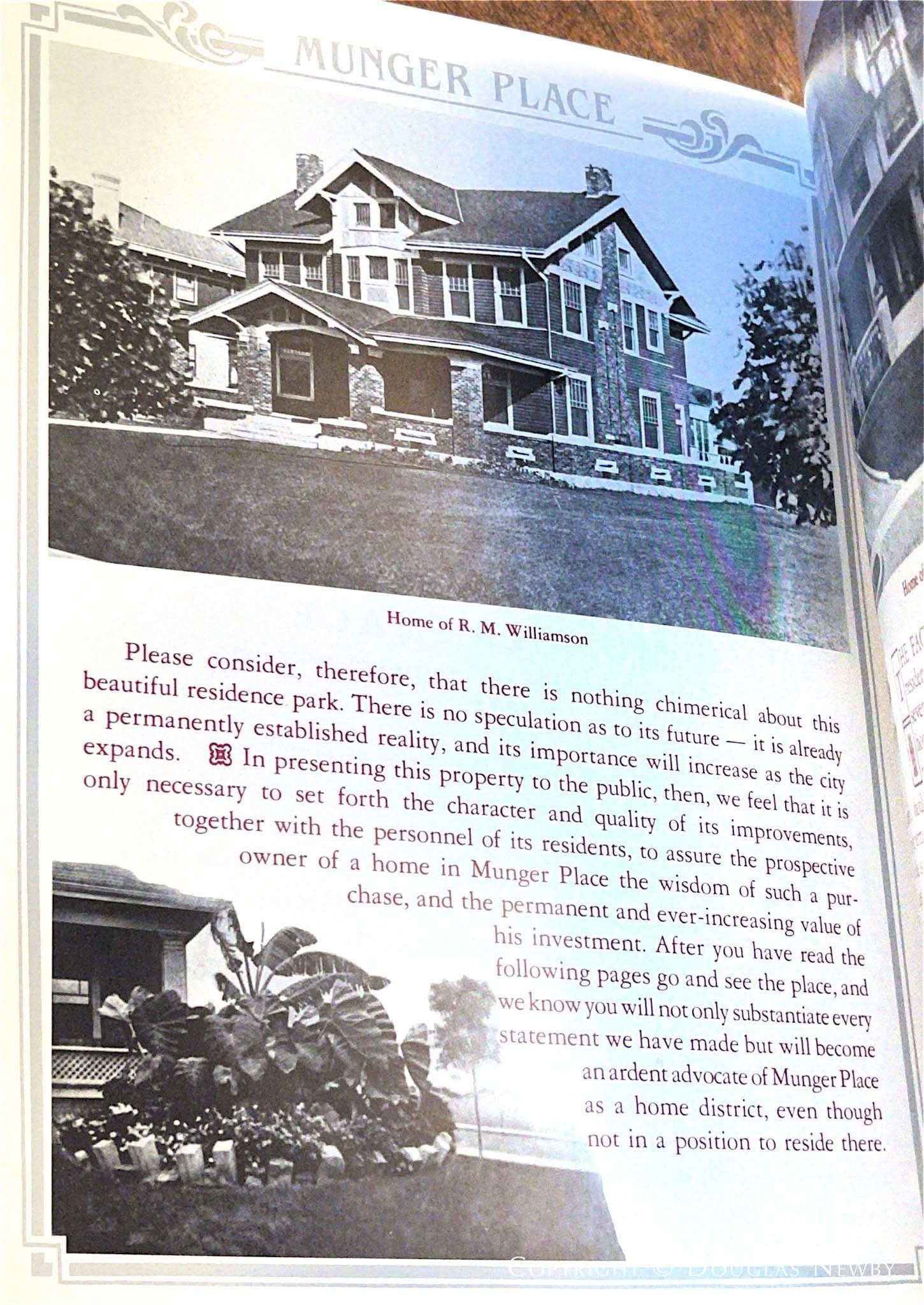

Original Munger Place Book Articulates Finest Residence Park in Southland

Neighborhood historian Fred Longmore and Old East Dallas advocate first brought the original Munger Place book to my attention. This original sales brochure was created to promote the Munger Brothers’ Munger Place, the first residential planned development in Dallas with architectural deed restrictions and a requirement that every home had to be designed by an architect. I reproduced this original brochure to share the architectural concept of Munger Place and how it impacted the development of other neighborhoods across Dallas. Understanding why Munger Place at one time was the most prestigious neighborhood in Dallas gave encouragement to those renovating and saving historic homes in Munger Place.

Dallas Restoration House of the Year Award Successfully Identified Historic Homes and Neighborhoods

There are many ways to identify and illuminate neighborhoods and homes that need to be saved. The Dallas Restoration House of the Year Award brought attention to historic neighborhoods and homes and helped define restoration to live in – restoration not as a historic museum, but restoration that accommodates the design of contemporary living. In 1979, I realized that the historic homes in Dallas were being renovated like the historic homes in Highland Park. Prairie style homes were becoming Georgian; Tudor houses were becoming French; porches were removed and turrets added. At some point a mangled renovation is as bad as tearing down a house. The Dallas Restoration House of the Year Award was created and was the first of its kind in the country. Every year the selection committee would include that year’s president of Dallas Chapter, AIA, which included architectural giants like the late Bill Booziotis, FAIA, Ed Beran, FAIA, and Overton Shelmire, FAIA. Architect Larry Goode, FAIA, served on the committee the year he was president. This year he is chairing the Preservation Park Cities Committee selecting the Top 100 Houses in the Park Cities that should be saved. The earlier committee also included each year’s ASID Dallas Chapter presidents, a local bank president, a magazine editor, and a neighborhood representative who looked at the homes nominated through the lens of their particular interest or discipline. Homes were nominated by the selection committee and Dallas neighborhood organizations. At the end of the day, a fascinating and vigorous discussion would take place selecting the winner. Three successive Dallas mayor presented the award each year, always accompanied by media and four television stations at a reception at the selected home. The extensive media coverage brought a better understanding of good restoration to live in and a better understanding of Dallas’ historic homes and neighborhoods.

I hosted the reception when a Winnetka Heights historic home received the Dallas Restoration House of the Year award presented by Mayor Starke Taylor. As the president of the Old Oak Cliff Conservation League said to me that afternoon, “This is the first time in Oak Cliff history that a Dallas mayor and four television stations had been together at an event south of the Trinity River.” When homebuyers know the inventory of historic homes and how to approach them, historic homes get saved.

A Guide to the Older Neighborhoods of Dallas Defined Neighborhoods and Their Historic Homes

A project I tackled early in my career showed me how an inventory of homes and neighborhoods brought greater respect for these homes and gave them a better chance to be preserved.

As a real estate broker, I was aware that homes had more value, credibility and desirability if they were in a defined neighborhood that had specific, well-known boundaries. At the time, Old East Dallas, Oak Cliff, and Oak Lawn were just large undefined neighborhoods often associated with neglected homes with little appeal.

For this reason, when I was on the board of the Historic Preservation League, I initiated the first book on the older neighborhoods of Dallas, titled A Guide to the Older Neighborhoods of Dallas. I chaired the committee that produced this coffee table-size book and was the principal author. I helped underwrite the book, along with dozens of homeowners and early neighborhood associations who also contributed by purchasing the book for themselves and their friends. We released the book with a Toast to Texas reception on March 2, 1986, for the Sesquicentennial. The book was a huge success. It was number two on the Dallas list of nonfiction books the same year author Elizabeth Forsythe Hailey’s book, A Woman of Independent Means, was number one on the national best-selling list. This was fun because Betsy Hailey’s grandfather was Joe Kendall, the developer and promoter of Junius Heights and played a major role in the Belmont Addition – two neighborhoods featured in A Guide to the Older Neighborhoods of Dallas. Several of the neighborhoods first identified in this book are now conservation or historic districts and the homes within them are protected from being torn down.

The book informed realtors, changed the ways they sold homes and raised the awareness of architectural influenes in Dallas. Before, realtors had been referring to listings on the M Streets as “gingerbreads.” After the book was published it became common for these historic homes to be referred to as Tudor cottages in Greenland Hills. This book also had an appendage that excerpted Virginia and Lee McAlester’s book, A Field Guide to American Houses, that defined the styles of the homes found in many of these Dallas neighborhoods.

A Field Guide to American Houses Became the National Authority on Residential Architectural Styles

The McAlesters’ book, A Field Guide to American Houses, became the “Audubon Bird Book” of house styles. The book increased people’s interest in the architecture of the homes and the styles of homes around the country. Since Virginia and Lee were both from Dallas and lived in Dallas, the book had an even greater impact on Dallas homeowners and the interest in preservation and historic architecture. This book also gave Dallas a high profile nationally as a city interested in preservation architecture. As people became more familiar with architectural styles, that helped save homes from being torn down.

The AIA Dallas Chapter’s 50 Significant Homes Project Created the First Residential Architectural Survey of Dallas

After working almost exclusively in the historic districts of Old East Dallas for 20 years, I turned my attention to the Park Cities because there was so little interest in architecture and preservation in Highland Park, University Park and Preston Hollow and the other estate areas of Dallas. I decided I could have even greater impact on preservation and architectural awareness if I devoted my energies to Highland Park, University Park, Bluffview, Preston Hollow and Turtle Creek.

In 1997, I proposed a project identifying 50 significant homes to celebrate the upcoming 50th anniversary of the AIA Dallas Chapter. I broached the idea with the chapter’s president, the late Bryce Weigand, FAIA. Bryce agreed and asked if I would chair this 50 Significant Homes project. I will be forever grateful to Bryce for all of his contributions to Dallas and the architectural community and for involving me in this project. I enlisted the participation of the presidents of the major Dallas cultural organizations for the selection committee. These included Deedie Rose representing the Dallas Museum of Art, Harry Robinson representing the Dallas African-American Museum, Bryce Weigand representing AIA, Rita Clements representing the Dallas Historical Society, Rick Brettell representing the Dallas Architecture Forum, and James Pratt representing the Greater Dallas Planning Council. Members of the selection committee each in turn recruited 10 or so people to nominate Dallas significant homes. We asked those selected to nominate houses to include the names of the architects that designed the homes, the year built, and other interesting information.

Over the summer, there were 100 people talking about and scouring the city to discuss, debate, and uncover historic and architecturally significant homes. Homeowners would comb through their attics to find original floorplans with the architect’s name. Research was conducted by people who were passionate about Dallas. The result was a city-wide survey and a list of architect-designed homes across the city spanning 100 years. The final selection of 50 significant homes took place in the Scott Lyons-designed home of Margaret McDermott, the project’s honorary chair. The selected homes were then announced at the last reception ever held at the Crespi Estate before Cinda and Tom Hicks took over this Maurice Fatio-designed home and renovated it. Architect Arch Swank was honored as Frank Welch spoke about him and his contribution to Dallas architecture.

As we hoped, the 50 Significant Homes project brought great attention to the Dallas AIA Chapter. It also brought great attention to Dallas as the place with the greatest collection of 20th century architecture in the United States. The current Preservation Park Cities Top 10 Homes were on the 50 Significant Homes list from 25 years earlier. The late Bryce Weigand’s former architectural firm partner, Larry Good, FAIA, is the current chair of the Preservation Park Cities Committee now selecting the top 100 Park Cities Homes that should be saved. I think Bryce would be proud that the 50 Significant Homes project he oversaw helped create the foundation for the list of homes Preservation Park Cities is compiling today.

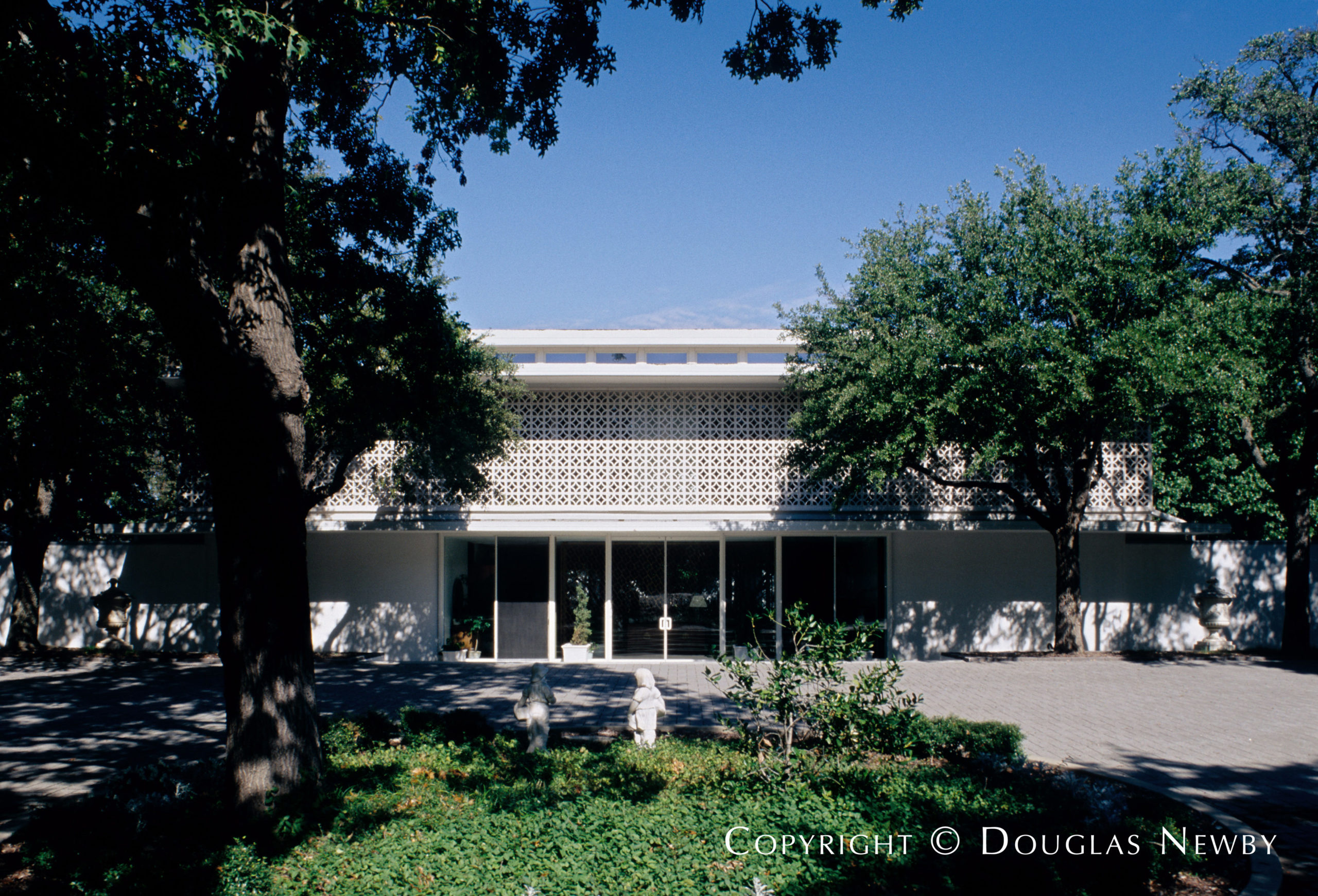

Further Illumination Saves Edward Durell Stone Designed Architecturally Significant Home

President of American Airlines Robert Crandall and his wife Jan bought this modern house at 5243 Park Lane when many thought it would be torn down, as it had been rented out for fraternity parties for several years. They did a great job stabilizing the house and renovations that made it attractive and livable. It was selected by the Dallas AIA Chapter as a 50 Significant Home; however, it still remained in jeopardy in 1999. This was a 40-year-old, 10,000 square foot modern home with only one bedroom that had been modified over the years. Solid concrete walls and asbestos made it more difficult to do the next extensive renovation. Also, at the end of the last century, even those that loved modern homes were skeptical that if they bought a modern home, there would be a market to resell. It was also sited on a one-acre lot on the most prestigious corner of Preston Hollow, making the demand for the lot very high. Illuminating the concept of the home and its merits by illuminating its architect Edward Durell Stone, the landscape architect Thomas Church and the interior designer T.H. Robsjohn-Gibbings gave Dallas a new appreciation for the home.

In addition, art and architectural patrons and cultural leaders, including Dr. Richard Brettell, former DMA Director, and the daughter of the original owners, Dr. Joanne Stroud, were invited to speak about the home to over 100 architectural advocates including the eventual purchaser. This renewed interest and endorsements by the tastemakers of Dallas brought forth several buyers. The home two years later was exquisitely renovated by then DMA President John Eagle and his wife Jennifer. The renovation architect was Russell Buchanan and interior designer was David Cadwallader.

This historic and architecturally significant home designed by Edward Durell Stone is a perfect example of how identifying the home and illuminating its architectural brilliance can save a home from being torn down.

Great American Suburbs: The Homes of the Park Cities – Dallas Identified Architect-Designed Homes in the Park Cities

In 2008, Willis Winters, Virginia McAlester and Prudence Mackintosh wrote Great American Suburbs: The Homes of the Park Cities, Dallas, a book that identified architect-designed homes in Highland Park and University Park. It is interesting that Virginia McAlester and I worked closely together on projects in Munger Place, specifically the revolving fund, and both of us spent most of our Dallas efforts in Old East Dallas. Independently, we both saw a need to bring greater attention to the architecture of Highland Park and University Park. Ten years after the 50 Significant Homes project of the Dallas Chapter, AIA, Virginia McAlester and Willis Winters, an architectural historian and Dallas City Park Director, wrote their book that identified architect-designed homes in the Park Cities. Almost everyone in the Park Cities had a copy of this book. It increased the prestige of the architect-designed homes they identified. While some of the homes published in this book and a few of the 50 Significant Homes have been demolished, many of these homes still stand, including Margaret McDermott’s Scott Lyons-designed home at 4701 Drexel that is now being renovated.

Every 10 Years or So a Fresh Initiative is Needed to Promote the Good Architecture and save homes in the Community

I am pleased Preservation Park Cities is creating a fresh list of the top 100 homes to be saved in the Park Cities. This effort is bringing renewed attention to the dwindling number of homes in the Park Cities that can still be preserved. I’m also pleased that many of these homes were featured in Great American Suburbs: The Homes of the Park Cities, Dallas. The top ten on this list were also previously identified on the 50 Significant Homes list I worked on in 1997. Good architecture stands the test of time! But new efforts must be undertaken with each generation to keep awareness alive.

Preservation Park Cities Top 100 Will Set Stage for Next Step in Saving Homes

Preservation Park Cities touting the Top 100 Homes that need to be saved will give momentum to the vital Step One of identifying homes that need to be saved.

Preservation is the Most Grassroots, Accessible Space for Individuals to Contribute to Their Community

Anyone can make a monetary contribution to any cause, but only a highly trained specialist can find a cure for cancer. In contrast, preservation is one of the few causes in which so many people can contribute with their interest, time and talents. Preservation can be impacted by individual initiatives to bring attention to and preserve historic and architecturally significant homes and neighborhoods.

The first step to saving homes is identifying the homes that need to be saved and their attributes. Whether it is one’s own home, a family member’s home, a neighbor’s home, or a home one has always admired, individuals can bring attention to these homes. Finding out about a home, even researching the home or just passing on information to friends enhances the profile and importance of that historic or architect-designed home.

In my next blog article, I will discuss step two through step five in saving homes.